Cocaine addiction, referred to clinically as Cocaine Use Disorder (CUD), is a complex psychiatric disorder defined in the DSM 5 a pattern of cocaine use leading to clinically and functionally significant impairment, such as health problems, disability, and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home [1].

Prevalence of Cocaine Use

In the United Kingdom, the use of cocaine, is a widespread concern. Approximately 1 in 11 adults aged 16 to 59 years (9.2%, or roughly 3 million adults) reported using cocaine at least once in the year ending June 2022. Among young people aged 16 to 24 years, the prevalence of cocaine use was even higher, with approximately 1 in 5 individuals (18.6%, or roughly 1.1 million adults) reporting use during the same period [2].

The Probability of Developing a Cocaine Addiction

Cocaine is a highly addictive substance which presents a significant risk of transitioning from initial use to dependence and addiction. One large data analysis of 54,573 participants found a 20.9% likelihood of a person developing a cocaine addiction from first use [3]. Another similar study of 11,449 individuals found that 15.6% of those engaged in cocaine abuse transitioned to dependence at some point in their loves, underscoring the substantial risk cocaine poses in leading to addiction [4]. Top of Form

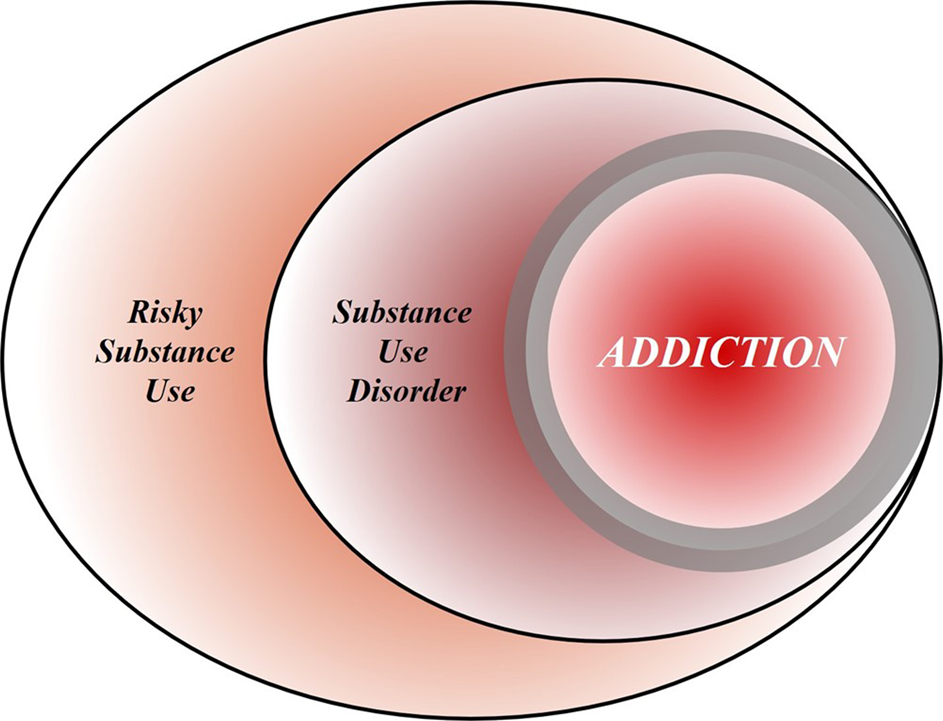

The Process of Addiction

The process of addiction can be understood through distinct stages, starting with recreational use, where individuals consume substances with few, if any, negative consequences. As recreational substance use continues, it may progress to risky use or abuse, characterised by increased quantity and frequency of consumption, as well as changes to the method of consumption, such as progressing from snorting cocaine to smoking or injecting. A Substance Use Disorder (SUD) tends to occur after prolonged risky use or abuse, and describes individuals who meet diagnostic criteria, categorised into mild, moderate, or severe cases based on the extent of impairment. Addiction is defined as a prolonged period of SUD in which individuals exhibit persistent difficulties with self-regulation of drug consumption [5].

The Neurobiology of Cocaine Addiction

Cocaine produces its effects by binding to the dopamine transporter, which inhibits the removal of dopamine from the synapse. This results in an accumulation of dopamine and an amplified dopaminergic effect, leading to the euphoria commonly experienced immediately after taking the drug [6]. However, over time, the brain adapts to this excess dopamine, causing a decrease in the high, a phenomenon known as tolerance [7]. Individuals may then increase their cocaine consumption to achieve the initial euphoric effects, which can lead to a vicious cycle of addiction.

Potential Treatments Cocaine Addiction

Cocaine addiction treatment approaches can be broadly categorised into three distinct types. Psychosocial interventions, which aim to promote abstinence through group and individual therapies. Pharmaceutical treatments, which aim to reduce cravings through medication. Medical treatments, which focus on involve on symptom and withdrawal management. It is important to note that currently, there are no FDA/NICE approved pharmaceutical or medical treatments for cocaine addiction. However, ongoing research offers promising insights and avenues for further investigation.

Psychosocial Treatments:

- 12-Step Programs (TSGs): These group-based self-help programs provide structured support networks and promote abstinence through increased accountability, spiritual and personal growth. Studies have shown that prolonged and increasing attendance of these groups increase the chances of remaining abstinent at 3-, 6-, and 12-month markers [8,9]. However, the data supporting TSG efficacy is often unreliable and therefore difficult to apply to larger populations.

- Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT): CBT helps individuals recognise and avoid triggering situations and teaches coping skills to manage cravings. Studies have found CBT to be more effective at promoting prolonged abstinence than TSGs [10] and reducing frequency of use than medication [11], and meditation [12].

- Voucher-Based Reinforcement Therapy (VBRT): VBRT uses vouchers for shops, cinemas, and restaurants to positively reinforce abstinence. It is often combined with other psychosocial treatments. Research shows that VBRT is more effective at promoting prolonged abstinence than CBT alone [13], and drug-replacement treatment alone [14]. However, this approach can become very expensive, especially at scale and over extended periods.

Pharmaceutical Treatments:

- Dopamine Agonists: These substances activate the same receptors as the abused drug, reducing cravings. Studies have found that dopamine agonists are significantly better at reducing cocaine use than placebo [15,16]. However, these potential treatments come with a significant risk of addiction/cross-addiction.

- Modafinil: A mild stimulant used to treat sleep disorders, modafinil also blocks dopamine transporters, reducing dopaminergic effects. In several laboratory studies it has been shown to be better at reducing the euphoric effects of cocaine than placebo [17,18]. However, in clinical trials the findings have been less promising [19].

- GABAergic Medications: Medications that influence the brain’s GABA system, reducing dopaminergic activity. Research has shown that these medications are effective at reducing cocaine self-administration in rats [20] and are better at promoting prolonged abstinence in humans [21]. However, of these medications include significant risk of adverse side effects such as fatigue, nausea and skin irritation.

Medical Treatments:

- Antibody Immunisation: Injectable vaccines containing ‘anti-cocaine’ antibodies that prevent cocaine molecules from entering the brain, reducing the dopaminergic effect. Studies have found antibody immunisation to be significantly better at reducing the euphoric effects of cocaine than placebo [22]. However, other research found no significant difference between immunisation and placebo at reducing cocaine use [23]. There is also a risk of vaccine-related injuries.

- Adrenalectomy: A surgical procedure that reduces the effects of stress hormones on addictive behaviours, reducing stress-induced cravings. Animal studies have shown adrenalectomy to be very effective at reducing stress-induced drug-seeking [24]. However, this surgical procedure in humans would likely do more harm than good, requiring people to have permanent hormone-replacement therapy.

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS): TMS is a non-invasive psychiatric treatment that uses electromagnetic pulses to stimulate specific regions of the brain associated with addiction. This treatment can increase the brain’s ability to rewire and adapt (neuroplasticity), helping to reshape and reduce maladaptive behaviours associated with addiction.

Research exploring the potential of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) as a treatment for cocaine addiction reveals promising results. High frequency (≥10Hz) rTMS targeting different areas of the prefrontal cortex has demonstrated positive effects in reducing cravings and improving various aspects of addiction. Several studies report significant reductions in cocaine intake [25,26,27,28], alongside improvements (sometimes immediate [25]) in self-reported cravings and withdrawal symptoms [27,29]. rTMS has also been shown to be effective in reducing symptoms of comorbid depression [27,30], which is common in people with CUD. These findings underscore the potential of rTMS as a valuable approach in addressing cocaine addiction. However, to solidify its role in addiction treatment, additional large-scale and long-term research is required to establish its total efficacy and determine the most effective treatment protocols.

Conclusion

Cocaine addiction is a widespread issue with significant social and health implications. While various psychosocial, pharmaceutical, and medical treatments have been explored, the effectiveness of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) in treating cocaine addiction is particularly encouraging. TMS is FDA/NICE approved and has shown efficacy in reducing cocaine use and cravings, offering hope for individuals struggling with CUD.

Author, Adam

Smart TMS St Albans Practitioner

References

[1] British Medical Journal. (2023, February 28). Cocaine use disorder. BMJ Best Practice. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/199

[2] Office for National Statistics. (2022, December 15). Drug misuse in England and Wales. Home – Office for National Statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/drugmisuseinenglandandwales/yearendingjune2022

[3] Lopez-Quintero C, Pérez de los Cobos J, Hasin DS, Okuda M, Wang S, Grant BF, Blanco C. (2011). Probability and predictors of transition from first use to dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011 May 1;115(1-2):120-30. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.004. Epub 2010 Dec 8. PMID: 21145178; PMCID: PMC3069146.

[4] Ludwing Flórez-Salamanca , Roberto Secades-Villa , Deborah S. Hasin , Linda Cottler , Shuai Wang , Bridget F. Grant & Carlos Blanco (2013) Probability and Predictors of Transition from Abuse to Dependence on Alcohol, Cannabis, and Cocaine: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 39:3, 168-179, DOI: 10.3109/00952990.2013.772618

[5] Heilig, M., MacKillop, J., Martinez, D. et al. Addiction as a brain disease revised: why it still matters, and the need for consilience. Neuropsychopharmacol. 46, 1715–1723 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-020-00950-y

[6] National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2020, June 11). How does cocaine produce its effects? https://nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/cocaine/how-does-cocaine-produce-its-effects

[7] National Institute on Drug Abuse (2018, June). Understanding drug use and addiction – drug facts. National Institutes of Health. Available at: https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/understanding-drug-use-addiction (Accessed: 02 November 2023).

[8] Samantha J. Lookatch, Alexandra S. Wimberly & James R. McKay (2019) Effects of Social Support and 12-Step Involvement on Recovery among People in Continuing Care for Cocaine Dependence, Substance Use & Misuse, 54:13, 2144-2155, DOI: 10.1080/10826084.2019.1638406

[9] Weiss, R. D., Griffin, M. L., Gallop, R. J., Najavits, L. M., Frank, A., Crits-Cristoph, P., Thase, M. E., Blaine, J., Gastfriend, D. R., Daley, D., & Luborsky, L. (2005, February). The effect of 12-step self-help group attendance and participation on drug use outcomes among cocaine-dependent patients. Science Direct. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10826084.2019.1638406

[10] Maude-Griffin, P. M., Hohenstein, J. M., Humfleet, G. L., Reilly, P. M., Tusel, D. J., & Hall, S. M. (1998). Superior efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for urban crack cocaine abusers: Main and matching effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(5), 832–837. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.66.5.832

[11] Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Nich C, Gordon LT, Wirtz PW, Gawin F. One-Year Follow-up of Psychotherapy and Pharmacotherapy for Cocaine Dependence: Delayed Emergence of Psychotherapy Effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(12):989–997. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950120061010

[12] Monti, P. M., Rohsenow, D. J., Michalec, E., Martin, R. A., & Abrams, D. B. (1997). Brief coping skills treatment for cocaine abuse: substance use outcomes at three months. Addiction, 92(12), 1717-1728.

[13] Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Foerg FE, Donham R, Badger GJ. Incentives Improve Outcome in Outpatient Behavioral Treatment of Cocaine Dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(7):568–576. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950070060011

[14] Silverman K, Higgins ST, Brooner RK, et al. Sustained Cocaine Abstinence in Methadone Maintenance Patients Through Voucher-Based Reinforcement Therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(5):409–415. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830050045007

[15] Grabowski, J., Rhoades, H., Stotts, A. et al. Agonist-Like or Antagonist-Like Treatment for Cocaine Dependence with Methadone for Heroin Dependence: Two Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trials. Neuropsychopharmacol 29, 969–981 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300392

[16] Mooney, M. E., Herin, D. V., Schmitz, J. M., Moukaddam, N., Green, C. E., & Grabowski, J. (2009). Effects of oral methamphetamine on cocaine use: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Drug and alcohol dependence, 101(1-2), 34-41.

[17] Dackis, C. A., Kampman, K. M., Lynch, K. G., Pettinati, H. M., & O’Brien, C. P. (2005). A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil for cocaine dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology, 30(1), 205-211.

[18] Robert Malcolm, Karla Swayngim, Jennifer L. Donovan, C. Lindsay DeVane, Ahmed Elkashef, Nora Chiang, Roberta Khan, Jurij Mojsiak, Donald L. Myrick, Sarra Hedden, Kristi Cochran & Robert F. Woolson (2006) Modafinil and Cocaine Interactions, The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 32:4, 577-587, DOI: 10.1080/00952990600920425

[19] Dackis, C., Kampman, K., Lynch, K. et al. A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Modafinil for Cocaine Dependence. Neuropsychopharmacol 30, 205–211 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300600

[20] Kushner, S. A., Dewey, S. L., & Kornetsky, C. (1999). The irreversible γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transaminase inhibitor γ-vinyl-GABA blocks cocaine self-administration in rats. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 290(2), 797-802.

[21] Kampman, K. M., Pettinati, H., Lynch, K. G., Dackis, C., Sparkman, T., Weigley, C., & O’Brien, C. P. (2004). A pilot trial of topiramate for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Drug and alcohol dependence, 75(3), 233-240.

[22] Kosten, T., Domingo, C., Orson, F., & Kinsey, B. (2014). Vaccines against stimulants: cocaine and MA. British journal of clinical pharmacology, 77(2), 368-374.

[23] Haney, M., Gunderson, E. W., Jiang, H., Collins, E. D., & Foltin, R. W. (2010). Cocaine-specific antibodies blunt the subjective effects of smoked cocaine in humans. Biological psychiatry, 67(1), 59-65.

[24] Caccamise, A., Van Newenhizen, E., & Mantsch, J. R. (2021). Neurochemical mechanisms and neurocircuitry underlying the contribution of stress to cocaine seeking. Journal of neurochemistry, 157(5), 1697-1713.

[25] Camprodon, J. A., Martínez-Raga, J., Alonso-Alonso, M., Shih, M. C., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2007). One session of high frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) to the right prefrontal cortex transiently reduces cocaine craving. Drug and alcohol dependence, 86(1), 91-94.

[26] Bolloni, C., Panella, R., Pedetti, M., Frascella, A. G., Gambelunghe, C., Piccoli, T., … & Diana, M. (2016). Bilateral transcranial magnetic stimulation of the prefrontal cortex reduces cocaine intake: a pilot study. Frontiers in psychiatry, 7, 133.

[27] Pettorruso, M., Martinotti, G., Santacroce, R., Montemitro, C., Fanella, F., Di Giannantonio, M., & rTMS stimulation group. (2019). rTMS reduces psychopathological burden and cocaine consumption in treatment-seeking subjects with cocaine use disorder: an open label, feasibility study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 621.

[28] Madeo, G., Terraneo, A., Cardullo, S., Gómez Pérez, L. J., Cellini, N., Sarlo, M., … & Gallimberti, L. (2020). Long-term outcome of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in a large cohort of patients with cocaine-use disorder: an observational study. Frontiers in psychiatry, 11, 158.

[29] Rapinesi, C., Del Casale, A., Di Pietro, S., Ferri, V. R., Piacentino, D., Sani, G., … & Girardi, P. (2016). Add-on high frequency deep transcranial magnetic stimulation (dTMS) to bilateral prefrontal cortex reduces cocaine craving in patients with cocaine use disorder. Neuroscience letters, 629, 43-47.

[30] Martinotti, G., Pettorruso, M., Montemitro, C., Spagnolo, P. A., Martellucci, C. A., Di Carlo, F., … & Brainswitch Study Group. (2022). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in treatment-seeking subjects with cocaine use disorder: a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled trial. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 116, 110513.